HAPPY FATHER”S DAY WEEKEND!

Back in the early 1990’s when my father was in his 90’s I wrote him this thank you letter on Father’s Day to express how much I appreciated all he had done for me and to express my gratitude for passing down his outdoor heritage to me. If your dad is still with you I hope you will do the same. Wait too long and you will regret that you didn’t take the time to do it.

Dear Dad,

Happy Father’s Day!

On this special day reserved to honor fathers, I want to thank you, long overdue as it may be, for one of the most valuable gifts you have ever given me – a love of the outdoors. You dispensed it to me in small increments over many years, and I cherish every moment of its giving.

My earliest memories are of weekends when you would take time out for long strolls with me down the abandoned country road that led to the Clark River near our house. It was just you and me, and I felt important. Those long afternoon hikes down “the old back road,” as we called it, were great adventures to me.

It was here that you taught me the names of trees and the ways of animals. On these walks, you instilled in me the value of all creatures, large and small, and that they all have a place in this world in which God has blessed us to manage. College degrees would prepare me for an outdoor career, but you gave me my first training in wildlife conservation.

My next big adventure was to accompany you on blackberry picking outings. We studied birds’ nests as we picked the bounty of the land, and when I would whine for help as thorn-covered blackberry canes clung to my clothing and skin, you patiently set me free with your big, muscular hands that briers didn’t seem to bother. How I wanted to grow up to be just like you.

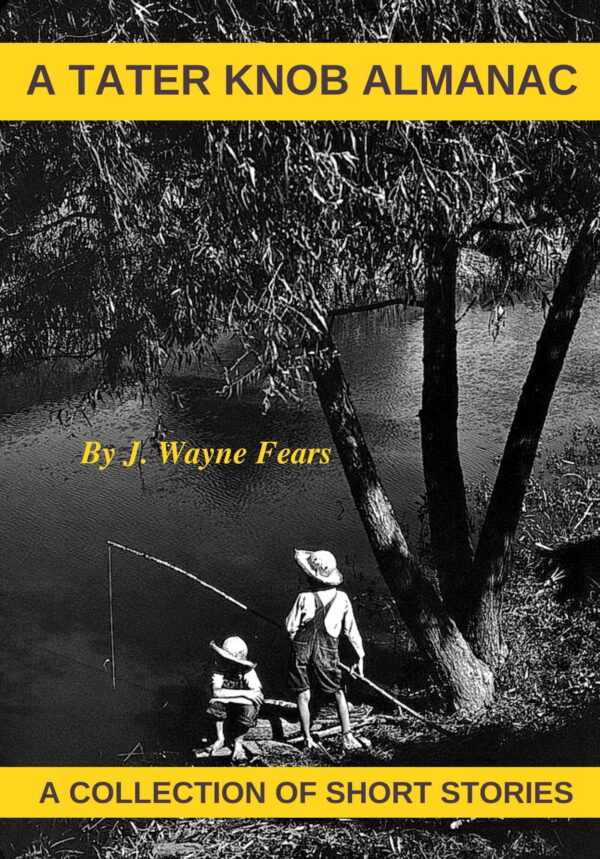

If fond memories have value, then I am rich. You discovered that your skinny, towheaded kid loved fishing so during warm weather; you would take me to our favorite outdoor spot, the small eddy of water below the long-forgotten dam that once had been the site of a gristmill.

The adventure started before we left home, as we always dug worms at the ‘sweet spot’ out in your garden. We packed the car the night before with our simple fishing tackle, a cast iron skillet, a hatchet, beans, and some cornmeal. I could hardly sleep the night before one of our trips. Every time I closed my eyes, I could see porcupine-quill float darting under the surface. I wondered if morning would ever come.

I have always been thankful that you didn’t start out my brother and me fishing with bass boats and fancy rods and reels. These modern trappings are far too complicated for small children, and I don’t think we would have ever enjoyed fishing as much as we did with our cane poles, hook, sinker, and float.

On these trips, you pretended to fish, but I now know you really spent the day teaching me to bait my hook, untangling my line from snarls that only a little boy can devise, and taking my ‘trophies’ off the hook.

Our shore lunch was always special. You taught me how to build a fire and the importance of eating the fish we caught. There seemed to be magic in your old black skillet, and I have never eaten better tasting fish than those you cooked. Camp beans and hoecake completed our menu, washed down with an RC or Double-Cola.

We usually sat around our campfire for a while after we ate, and you talked about things that

were important to me. We solved many of my problems during those chats, and I got a lot off my little chest spending that time with you.

Perhaps today, if more fathers were like you, children wouldn’t turn to distractions such as drugs. Thanks, Dad, for being there when your little boy needed you.

About the same time, you took the time to introduce me to shooting safety with my first BB gun.

I remember you teaching me to treat it with the same respect given to firearms. Your talks about the responsibility of gun ownership molded my behavior and have stayed with me ever since.

I remember our first early morning squirrel hunts clearly. During the first years, I only followed you, dreaming of the day when I would have my very own .22 rifle. With visions of mountain men in my head, I would stumble along, tripping over vines and stepping on sticks that would crack like a firecracker. I must have sounded like a truck coming through the woods. What patience you exercised! I am sure I messed up many hunts for you, but you smiled your way through my learning years.

When you introduced me to one of your friends as your “hunting buddy,” a rush of pride would flow through me. It gave me a much-needed feeling of self-confidence.

Your wisdom showed when I got my first ‘real’ rifle. You could have gotten me a fast-shooting autoloader with a riflescope, but you didn’t. It was an old Remington Model 33 single shot with open sights. With this rifle, you taught me that marksmanship was far more important than firepower. Besides, cartridges cost money, and we did not have a lot of that.

I remember so well the lessons you taught me about the respect we owed the game we were hunting and that the first shot should always be all that was necessary. At the same time, you taught me the importance of finding the game we shot so that we could eat it. I remember squirrel hunts where the morning was spent looking for one fallen squirrel. Good sportsmanship was something you showed me by example.

There are so many special times I need to thank you for, such as the summer nights when you would sit out in the backyard with me under that old hedge apple tree, rather than watch TV, and talk about hunting. It was here that I first leaned about game management and the role hunting played in keeping game populations healthy. In your gentle way, you instructed me in the importance of obeying game laws and taking care of the natural resources with which God blessed us.

I wonder how many fathers and sons or daughters will sit under a tree in their backyard tonight and talk about the outdoors. I am glad we didn’t miss out on those talks.

As I was growing up, I used to wonder if it was necessary to be as nice as you were to the landowners on whose land we hunted, fished or camped. I remember you always made sure we had permission to be there, even if we had been allowed before. You were so conscious of where we left the car so we wouldn’t block a road or park on a newly planted crop. We always closed the gates and were careful not to damage fences when crossing them. To drop a candy wrapper on the ground was almost a sin in your eyes. Now that I am a landowner, I appreciate what you taught me about outdoor ethics.

I owe you thanks for many more things. The best way I can say it, other than with this letter, is to pass along these same values to your grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

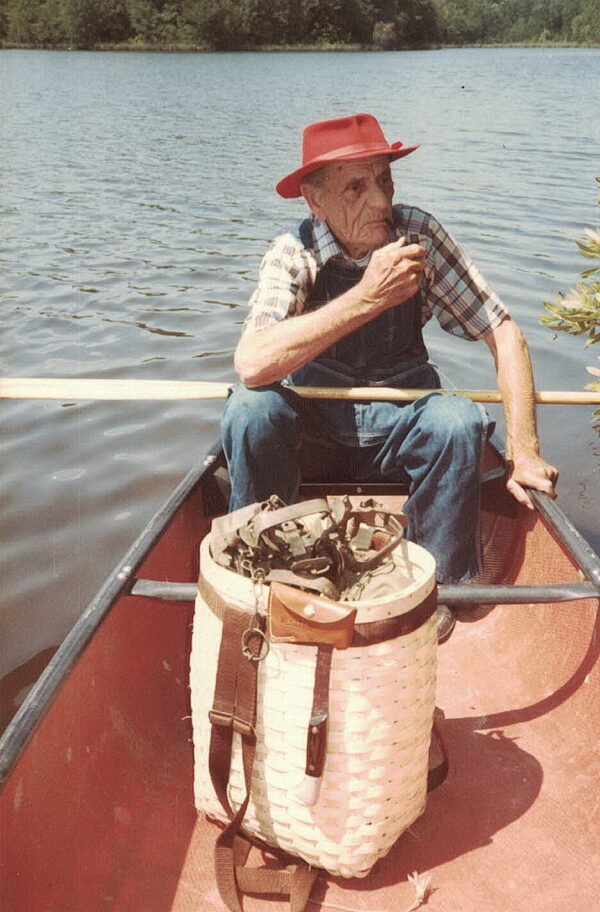

Dad, I consider it a blessing to have had you as my father, and every time I see a fish break the surface of a mirrored lake or hear a spring gobbler or see doves flying against a sky bathed in the gold of a sitting sun, I think of you and say a silent “thank you, Dad.”

Love from a grateful son,

Wayne